There is a lot of confusion on Palliative Sedation and there has also been a lot of debate on the ethical concerns around this. We unpack the concept of Palliative Sedation and when it is appropriate to consider.

One of the central goals of Palliative care is the relief of suffering and pain. Many terminal patients despite being on heavy medication for symptom control have intolerable pain possibly from their underlying disease or adverse effects of their treatment towards the end of life (typically the last few days before death). One aspect of Palliative care helps address the suffering of terminal patients during their last days. This area is known as Palliative or Terminal or Controlled Sedation.

Palliative sedation is the use of medication to reduce the severe suffering of the patient by administering sedative drugs thereby reducing consciousness. Suffering (also termed anguish or distress) is defined as the sense of helplessness or loss in the face of a seemingly relentless and endurable threat to quality of life or integrity of self.

| “‘Palliation sedation’ is a widely used term to describe the intentional administration of sedatives to reduce a dying person’s consciousness to relieve intolerable suffering from refractory symptoms.” |

The right time

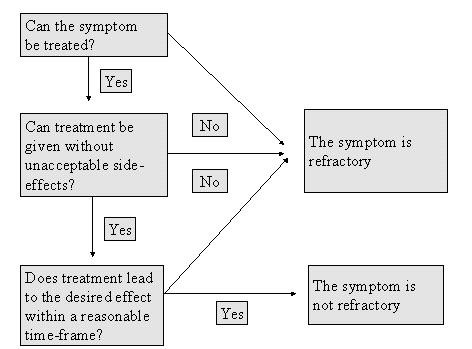

It is imperative to understand when palliative sedation should be considered. Palliative sedation can only be applied upon identification of one or more refractory symptoms in a patient. So first let’s understand what refractory symptoms mean. A refractory symptom is defined as any symptom that cannot be effectively controlled despite several aggressive efforts to identify a tolerable therapy which does not compromise the consciousness of the patient.

In cancer patients, refractory symptoms can include symptoms caused by the malignancy such as pain, uncontrolled vomiting, delirium, shortness of breath, agitation, seizures, myoclonus (involuntary muscle jerks or spasms), etc. Besides cancer, patients with COPD, Heart failure, and Neurological degenerative diseases can also exhibit refractory symptoms. In most instances the symptoms are neuropsychiatric, often non-specific but described as insufferable.

Criteria for diagnosis of a Refractory symptom must include that further treatments (both invasive and non-invasive) are:

- Unable to provide any relief

- Can lead to acute or chronic morbidity

- Not likely to provide relief in the acceptable time period

Figure 1: Criteria for a Refractory symptom.

Upon careful discussion in consultation with the Palliative Team, a patient can be considered for the Palliative Sedation Therapy (PST) with correct informed consent. At this point, the care settings of the patient must be evaluated before commencing PST. This setting can be the patient’s home, hospice or hospital equipped with medical supplies, machines and nursing staff for dosing and continuous monitoring.

The ethical implications

The discussion of sedation towards the end of life started about 30 years ago. There remained two schools of thought on the confusing and misleading terminology itself. Many argued whether “terminal sedation” was the right term as it can be misconstrued as the sedation being terminal. The term was replaced by “Palliative sedation therapy” later, which was more acceptable and appropriate.

It was defined by Broeckaert in 2002 as “the intentional administration of sedative drugs in dosages and combinations required to reduce the consciousness of a terminal patient as much as necessary to adequately relieve one or more refractory symptoms.” It was consensually agreed that the role of sedation was to reduce suffering without intending to reduce the patients’ lifespan.

The legal and ethical dilemma surround sedation stems from multiple issues. One of them being the psychosocial suffering. Physical pain often overlaps with psychosocial and existential pain which is subjective to the patient. With such pain, it is harder to differentiate if the symptom is refractory. Even though, such symptoms are invisible or immeasurable, they are profound for the patient.

Remember Suffering is a personal experience! |

The intention is always beneficence or the aim to do good and non-maleficence i.e.do no harm to the patient. The effect of the good should and must outweigh the bad effects as stated by the doctrine on double-effect. This is particularly important in understanding the difference between sedation and euthanasia or assisted suicide.

|

|

Palliative Sedation |

Euthanasia |

|

Intention |

Control the refractory symptoms | Ending life |

|

Method |

Giving precise dose of sedatives to control symptoms | Giving a lethal dose of drug |

|

Result |

Relief of suffering | Death |

|

Cause of death |

Natural progression of the underlying illness | Medications administered |

Autonomy is the right of the patient to make decisions about their health care without any outsides influences of the health care providers. When a decision (to accept or reject a course of action) is by the autonomous patient, it is termed Informed Consent. However, the complication arises when the patient is unconscious or mentally incapacitated. In such cases it is difficult to judge the extent of the patient’s suffering. Many feel that sedation is more beneficial to the family members and doctors than the patient and can lead to cases of abuse. One must also take into account the side-effects of sedation such as respiratory depression.

Since no concrete rules can be applied to patients, Palliative sedation relies on a set of guidelines that can be approached for individual cases taking into account refractory symptoms, life expectancy, level of sedation, quality of life and formal consent.

Keep the patient in mind

The goal of palliative sedation must focus on maximizing benefits and minimizing the risks for the patient. There must be a detailed discussion between the patient, his Palliative team, family members and care providers for the best course of action. Remember to respect the patient’s autonomy if he is mentally capable. Any debate on the risk-benefit assessment must be carried out before initiation of PST so there is complete consensus in the decision-making process. Make sure to have a plan for ongoing support and communication.

References:

- Twycross, Robert. “Reflections on Palliative Sedation.” Palliative Care: Research and Treatment, Jan. 2019, doi:10.1177/1178224218823511.

- Broekaert, B and Olarte, JMN. “Sedation in palliative care: facts and concepts IN: Ten Have H, Clark D, eds. The Ethics of Pa2007-12-07 University Press 2002:166-180.

- Fraser health. “Refractory Symptoms and Palliative Sedation Therapy Guideline.” Jan. 2011, doi: http://www.cspcp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/RefractorySymptomsandPalliativeSedationTherapy-Fraser-Health.pdf

- “Definition of Refractory Symptoms.” Stanford School of Medicine. Doi:https://palliative.stanford.edu/palliative-sedation/definition-of-refractory-symptoms/

- Palliative Sedation: When Suffering Is Intractable at End of Life. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. October 2017, Volume 19 Number 5, p 394 – 401 doi:https://www.nursingcenter.com/cearticle?an=00129191-201710000-00003&Journal_ID=260877&Issue_ID=4317552

- Olsen, Molly L et al. “Ethical decision making with end-of-life care: palliative sedation and withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments.” Mayo Clinic proceedings vol. 85,10 (2010): 949-54. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0201

- Juth N et al. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) framework for palliative sedation: an ethical discussion. BMC Palliative Care 2010, 9:20. DOI: 10.1186/1472-684X-9-20.