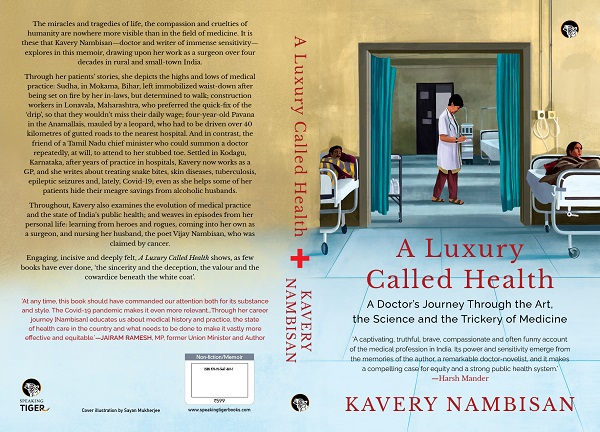

Dr Kavery Nambisan, eminent surgeon and novelist, in her latest book ‘A Luxury Called Health’ writes about her compelling medical experiences in rural Indian communities and talks of the key tenets of doctor-patient relationship. She dwells on medical ethics and corporatized health care.

Your latest book ‘A Luxury Called Health – A Doctor’s Journey through the Art, the Science and the Trickery of Medicine’ draws on your work as a surgeon over four decades in rural India. Why did you opt for rural healthcare at the beginning of your career?

I spent my early childhood in our village home (Madikeri, Kodagu (Coorg) district, Karnataka) and went to school there. Even later, when we lived in Delhi, we always went back on holidays. Ours is a farming community, so the roots are strong. Electricity came to our home just before I joined medical school. I think there were two or maybe three doctors in the entire district. But even so, I had no definite plans to work in a rural area and that first decision to work in Bihar was because I was asked by the catholic mission hospital there, if I could help for a short while. I truly loved the experience and the challenges if offered. So after Bihar, it was a decision to carry on working in rural areas.

The title of the book says ‘Art, Science and Trickery of Medicine’. Could you briefly elucidate some of these facets of medicine?

The easiest way to understand this subtitle would be to read the book! The ‘Science’ of Medicine is taught to us during our training period. The other two cannot be taught. Medicine is ‘Art’ because a doctor does not rely solely on facts about the body and its functions. The mind uses the knowledge based on an understanding of the uniqueness of each patient. There is a creative use of knowledge, intuition, imagination and empathy. By ‘Trickery’, what I mean is an astute understanding of human follies and foibles which make each person interesting (and at times infuriating.) One must at times be tricky enough to ride the bumps.

What are the primary challenges and rewards of working in rural communities?

Rural communities everywhere come with a human warmth and kindness that feels like the warm glow of fire when you are cold. They are also very inquisitive and at times quite impossible to please. If they have not benefited from your treatment, they will tell you. However, the challenges are many: You may be the only surgeon who has to cater to a large area; you may not have anyone to discuss difficult cases with. And if something goes wrong, there is no one nearby to help you. This motivates a rural surgeon to keep abreast of medical progress, by reading, learning from colleagues who work in higher centres and by undergoing training as and when possible. I went back to the UK a few times to learn as much as I could to help me become skilled in different branches of surgery.

At the same time, a rural surgeon must know her limitations. One learns from experience.

What contexts or situations in rural India have typically left a deep impression on you?

The wretchedness of extreme poverty is unforgettable. As also the basic decency and dignity of ordinary people, their toughness and courage in spite of being victims of injustice. We see this not only in our villages but also in the slums that house those who make it possible for us, the well-to do, to live in comfort.

What would you consider big opportunities and positives that can motivate health professionals to take up practice in the rural sector?

If you like to chart the course of your career using your own compass, you will find rural work very rewarding. It is more risky, more adventurous, more challenging and more fun. You earn considerably less than those in bigger centres but definitely enough to keep you comfortable, give your kids a good education and so on. I am grateful because I could enjoy my work. What could be more important?

If you change one aspect of rural medical setup, what would that be?

Make sure that the doctors who go to rural areas are well aware of what to expect. More or less. The living conditions, schools, recreational avenues, these are all factors which affect the quality of one’s life. It is the responsibility of the employer to make provisions for them. Doctors do not always find it possible to adjust to rural conditions. When I was working in rural Uttar Pradesh in Vrindaban, we had travel to Mathura 14 kilometres away, on a cycle rickshaw or by bus, in order to see a movie. Mind you, it is better not to know too much. I mean – I would not have ventured into Bihar if I had been told that I would be spending lots of nights digging bullets out from inside the belly. Generally, a doctor should have a pretty good idea what to expect.

Here is one more important aspect to keep in mind: To fashion rural hospitals on the image of those in cities is foolhardy and impractical. The majority of rural people cannot afford expensive treatment; they are hardy and generally more healthy than those in cities. A good rural surgeon or physician must be adept in clinical diagnosis based on clinical examination of the patient. Only very rarely are procedures like CT or MRI scans or a colonoscopy are necessary. A rural doctor has to learn to resist the temptation to ask for expensive investigations, while also knowing who among the many patients might need such tests.

Could you spell out 5 best practices to improve doctor-patient relationship in today’s society?

- Be sincere in your work at all times.

- Have a rapport with every patient. Think of them as someone’s brother, husband, grandma, daughter – and give as much concern as you would to your own.

- Be kind but firm. Do not let any patient or attender break rules which might be detrimental to the work environment or to other patients.

- Listen to what the patient has to say even if it seems irrelevant and gently steer them back to their problems. Patients need to be listened to.

- Do the best you can for each patient. Tell them when you cannot help them and help them find the right place at a higher centre.

As a distinguished surgeon, you must have encountered many difficult situations and grave illnesses. How do you approach discussing unpleasant topics with patients and their families?

Be direct and clear. I usually draw simple diagrams to explain what an operation involves and encourage patients to ask questions. Even when the illness is a serious one, the patient has a right to know. So except in rare instances, I explain the facts and the need to stay positive in order to fight the disease. Listening to the patient and speaking to the family are very important. We need to give it our full attention.

At the end of the book, you have dedicated a chapter to your late husband, the poet Vijay Nambisan, who died of cancer. You were the primary caregiver for him. What was your learning from that experience?

It is very hard to see your loved one suffer from an illness such as cancer. For a doctor, it becomes entwined with the knowledge you have of the illness and its progress and that makes it doubly hard. But whether you are a doctor or no, the struggles are no different. You fight to save the person and at times you fail.

Your book dwells extensively on ethics in the medical institution. How can we ensure complete safety of patients in healthcare settings today?

It is the biggest concern. How to instill the value of medical ethics in doctors? In India, we have made an effort to set up the department of Humanities in medical colleges. Even now, there are only a few who teach Humanities and the students can decide if they want to make use of it or no. At St John’s Medical College in Bangalore, where I am an honorary faculty member, we engage them in Literature, History, Art, film making, music and issues of social concern. Not many among seasoned doctors are enthused by the introduction of Humanities but over the years, it has proved to be very rewarding.

One of the reasons why I am appalled by the burgeoning of corporatized health care is that corporate sector stands for profits but health care should never be about profits. A Nationalised Health Service which is subsidised by the government is essential if we are to reach people at all levels.

Lastly, has your medical career influenced your writing?

I am usually asked, at readings and conferences, if my medical career has influenced my writing. The answer, of course, is yes. It is a powerful stimulant in fiction and has helped me connect with people in every mood or situation.

Only once, at the University of Columbia in the US, I was asked by Gayatri Spivak (Indian scholar, literary theorist, and Professor at Columbia University) if my writing of fiction has influenced my medical work. Yes, indeed it has. Through the writing of novels, I have explored lives in so many different ways by trying to reach the innermost depths of human emotions. I also read very widely. This has surely helped me develop sensitivity which is essential in patient care.

(Dr Kavery Nambisan has written seven novels, including The Scent of Pepper, The Story That Must be Told and A Town Like Ours. She has also written several book for children.)