Shormistha Mukherjee, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2018, authors a book about her treatment and struggles with disarming honesty and hilarious observations. She wishes to emphasize that cancer doesn’t have to be a death sentence as depicted in most films and books. Read her insightful interview.

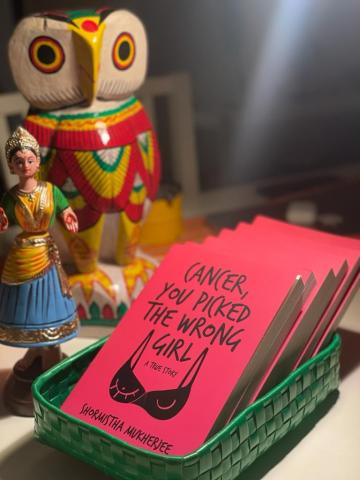

Congratulations on the success of your book ‘Cancer, You Picked the Wrong Girl’. It is a brilliant blend of health and humour. What motivated you to write this book?

Actually there were two driving points. When I got sick, I had never met anyone who had had breast cancer. I wanted to go through a personal memoir, to share somebody’s narrative who had been treated here, not treated abroad. But I couldn’t find anything. There was no account of the whole journey. Hence I felt a strong urge to share my experiences.

Secondly, when I was diagnosed, I didn’t want to keep my illness in a shroud. I wanted to be able to tell everyone what I was going through. So I created a blog. And as I started writing, more and more people began responding to it. I was also approached by Harper Collins, my publishers, to consider writing a book. I had barely written six pieces, but I thought if my writing can bring solace to people, then maybe I can just write a book. That’s how it all got moving.

There are many books that have been written on breast cancer by survivors, most being sombre chronicles. Yours is brutally detailed with incisive humour. Did it take a lot of courage to publicly share a no-holds barred account of your personal illness?

When I started writing the book, I told my editor that I am going to be as honest as I can in the book- even if it is going to be hard for me. If people are going to turn to my book for comfort and information, I had to lay myself bare. How could I not say everything, how could I pick and choose what to say. People are so uncomfortable talking about cancer. We seldom have conversations about, for example, inverted nipples which could be an early telltale sign of cancer, or the awkwardness of your breasts being squeezed for mammography, or the dilemmas of breast reconstruction, or anal fissures during chemotherapy, and so many other nitty-gritty details that we skim over. But I was quite determined not to hold back anything.

In your book, you have delightfully interspersed funny observations on procedures like mammography, chemotherapy, radiation, breast reconstruction, etc. Does humour empower you especially when facing awkward body situations or illnesses?

The funny part is that I never thought of humour like that. I tend to live in my own head. I observe a lot of things. Even if I am in that situation, there are things that I will notice. And I love writing. So I’ll come back and write about it. I’ll file it away in my brain. Because even in the scariest and the darkest moment, there are things that are absurd. For me sometimes those would come out. I really wrote it exactly how I felt at that moment. Like during the mammography, I kept thinking about the technician doing the procedure… “Imagine holding so many breasts in a day and pushing it between the plates. I wonder what the lady tells her friends and relatives about her job. ‘What is this job I have?” Or the sight of glistening bowls at the MRI made me wonder how perfectly dahi (curd) would set in it. Or at the PET scan, where there were La-Z-Boy recliners with a fluffy blanket. “I kid you not, some popcorn and I would have thought I’m at a personal movie screening where they take blood instead of tickets.” Observing all this helped me keep my sanity. They were like healthy distractions.

You treatment seemed severe with complete mastectomy, lymph node dissection, 16 rounds of chemo and gruelling side effects. What kept you going in the darkest of hours?

You know it may sound weird…but I kept thinking myself to be in one of those old war movies, where prisoners are kept in solitary confinement and life is like a drill. You have follow a certain schedule and rhythm. For some reason I kept thinking I am in that zone. I just need to follow one routine. To eat, sleep, workout, read, watch movies, etc at a fixed time. So if I was having my lunch at one o'clock I would have it at the same time, no matter what. I would wake up at the same time. I think it kept me clear headed to a large extent.

I was also very lucky to be surrounded by amazing family, friends and husband. I had all of them to rally around me. So I think however dark it is, it is never that dismal when you are encircled by people who love you.

Further, I realised, I am not going to die. I am going to survive this. I would tell myself all that I have to do is to be patient, however hard the situation maybe. I am just going to wait for the light at the end of the tunnel and I know I am going to get there. I will take each day as it comes. That was it for me. I just had to keep my eye on the goal.

You have mentioned many coping mechanisms during your year-long treatment like yoga, flower therapy, meditation, painting, etc. Which brought you most comfort?

- Definitely a routine worked for me. It also helped me fill my days and fill my mind.

- Yoga helped me a lot. But to be very honest there were days I could not do anything. I would just sit on my mat. But that was also okay. The thought that I trying to help my body was itself empowering. And my teachers were very kind. Some days they would push me a little, other days they would follow relaxation techniques.

- I also did a lot of meditation. I would listen to something that calmed me. Just before my surgery, I listened to a lot of mediation recordings. I kept listening to it because it was so relaxing.

- I did pottery. Pottery was not necessarily about creating something, but just squishing and squelching and being able to put my hands in mud. I cannot tell you what a relief it was just to feel the mud.

- I also took to walking. There is a park by the sea near my house and I would walk barefoot. Again that helped me. Just being in touch with myself, with the earth, the sky, the sea was very therapeutic.

Was it difficult to revisit the memories and write about it?

Sometimes it was difficult. Sometimes, my husband would come back from work and find me crying on the dining table. I can’t do it, I would sob. But yes, of course, it was hard.

What was one of the surprising things you learned in writing this book?

You know when you are going through the treatment, you are so focused on surviving the experience. But when I was writing the book, I had a more objective viewpoint. Something that struck out glaringly was when I went for my MRI…I realised that at most places there were male doctors or attendants. At that point I didn’t think about it, but when I wrote the book I was like now imagine if a woman who has come from a conservative setup how hard it would be for her. First she has to face the trauma of being diagnosed with cancer, second she has to face the male gaze everywhere. She has to bare her breasts to a whole bunch of strangers who are sitting behind the desk laughing, chatting and talking. I never felt it then, but it is only when I wrote the book it struck me. We need to look at the medical ecosystem and infrastructure more from the female perspective.

Could you spell out certain sensitive ways to strike up a conversation when you meet someone with breast cancer or other illnesses?

I think the first thing is not to express shock and alarm. It is very important to be calm before a person who has just been diagnosed with an illness, or even before a patient. Also I think one should not rush in with advice. You don’t have to launch off into how your aunt or uncle were feeling under similar circumstances. Sometimes you can quietly listen to the patient. I think the problem arises when people are unsure of what to say, then they land up blabbering. We don’t leave any silence or any space. We just quickly fill everything. The best thing to do is to leave that space for the person to tell you how they are feeling or what would they want from you.

Could you list 3 books on cancer that provided you warmth and wisdom?

The only book I read during my treatment was Yuvraj Singh’s book gifted by a friend to me. I read the book because I knew he has recovered from it. When I was sick, I didn’t want to read anything that would disturb my equilibrium. I would rather read fiction or a whodunit.

I am sure many of your readers would love to know what do you do and how are you now?

I am a co-founder of a digital agency.

As far as my health is concerned, I am doing great. I am back to work. I eat sleep normally. I have resumed one of my favourite pastimes - cycling. I have also just completed a course whereby I can now take people on History and Heritage tours.

I have to report for check-ups every six months. I am a bundle of nerves, three days before my hospital visits, but I survive.

And finally, what do you want your readers to come away with after reading your book?

This message is not just for patients. It is for anyone who reads my book. I want to tell everybody that cancer is not always a death sentence. With medical science progressing, if you are detected in time, you do have a chance to be treated, recover and lead a good life. I want more people to understand that. Because for too long, this narrative in movies and books that cancer is a death sentence needs to be changed. I think that has gone on for way too long. Whether it is in ‘Fault in Our Stars’, or ‘Anand’ or ‘Ae Dil Hai Mushkil’.

Secondly, there should be more conversations and awareness created around cancer, especially breast cancer. Instances of breast cancers are huge. These are not numbers to be ignored. I mean it is shocking. Now when I look back, I question myself… why did I not know this. So women should talk about it to their friends, sisters to spread awareness.

I think that would be the biggest thing I would want people to take away from this book. I have had so many women tell me that they read the book and they scheduled a mammogram. Or they read the book and they got themselves a medical insurance. I would say … perfect. This is what I want the book to be.