Prof Anita Ghai, a leading disability rights activist and academic reflects on her own life, her life with polio, rheumatic heart disease and breast cancer and her persistent struggles with undesirable societal attitudes towards disability.

‘How come you had polio? Were you not vaccinated? Why was your mother not more careful?’ These are some questions that always haunt me. Of course, there are many others such as ‘why me?’ that all of us always ask ourselves.

But what can one reply to these questions? In an effort to defend my mother, and indeed myself, I respond by reeling out factual information about how the polio vaccine came to India in 1959, one year after my birth. There was little that both my parents could have done.

Disabled, Not Defective

But the fact remains I am a ‘person marked with polio’. I have no memory of an “able body.” Hence, the world that I grew up in gave me a message that to be disabled is to be defective and that disability in a conclusive analysis is intrinsically disapproved of. Not surprising therefore, it took me a long time to own my polio and disabled body and accept that I was disabled but not ‘defective’.

While I was not left out of familial interactions, the discourse within the family as well relatives and friends that I grew up hearing was of curing the ‘poor girl’— ‘itni soni hai par dekho na kismet ko’ (‘she is so pretty but look at her luck’). The notion of beauty linked to femininity was yet another aspect that I needed to confront while coming to terms with my disability. I still remember that as a child, passing as a “normal woman” motivated me to beautify and normalise myself by wearing tights or long pants, just so I could hide the leg braces. I realised soon that these changes would not transform my gait.

Quest for "Cure"

While the disability experience records the pain and anguish of disabled lives, families and their disabled children both learn to resist the stigma of disability. My family was affected by the polio story, and the theme song was a ‘quest’ for a ‘cure.’ All through my life, I have negotiated with shamans, gurus, ojhas, tantric priests, and faith healers, as well as miracle cures – all to ensure that I could become a part of ‘normative’ hegemony.

My first recollection was when I was buried neck-deep in ‘curative’ mud at the tender age of eight during a solar eclipse. My trauma embedded in my unconscious re-emerged through the free associative recall of psychoanalysis some years later. My parents once took me to the Balaji Temple in Mehndipur, a famous Hindu pilgrimage centre in Rajasthan, India. At this temple, I also saw that some people were shackled in chains, a form of treatment for serious possession by a spirit that makes the ‘victims’ violent. As a child I remember being traumatised by this sight and at the thought that the temple authorities might chain me too.

In yet another instance, I recall going to Sohna, where I was made to bathe in the hope that the sulphur water would take away my polio and make me whole again. Both spoilt and coddled, I looked upon polio as my cross to bear and as a gift. However, the challenges that my physical condition presented continued and had to be coped with. As a young girl I remember falling down on innumerable occasions. The physical hurt, though tough at times, was always less painful than the look of fear on the faces of those around me.

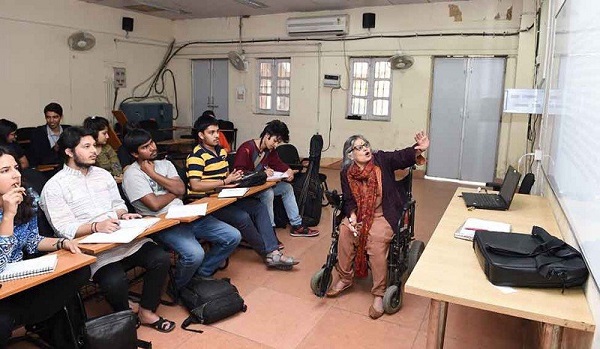

In picture above, Prof Anita Ghai in a wheel chair conducting a class

In an effort to understand my pain and to be rid of it, I would often conjure up different stories. My fantasy was that my condition could disappear in a variety of ways – by praying hard, a chance earthquake in which I would fall and get up as a non-disabled person. Every night (before bedtime) I would think of a fairy who would tell my body that when it woke up, the polio would be cured.

Determined To Strive and To Thrive

But there were hopeful moments too. I spent a lot of my childhood with my grandmother. One of the most important stories she told me was of the Buddha, which (for me) became symbolic of the experience of suffering and its containment. In my formative years, this helped me believe that suffering was normal and disability was a ‘form’ of suffering, inherent in every human being. Not surprisingly, the child in me had several questions, which my parents had to deal with constantly. My parents’ way of resolving my questions was with counter questions. I often asked my father, ‘why me?’ His reply usually would be, ‘Why not you? Are you not God’s gift?’ I am not quite sure I understood the question or the answer but it definitely raised more questions and awareness. I truly believe that my parents helped me learn some very powerful values at a very young age – the determination to strive and to thrive.

In the pic above Prof Anita Ghai is cooking in a kitchen while seated on a wheelchair

Yet the issue of access to places and spaces continues to bother me. I have lived through countless assurances that a conference or seminar I would be attending is on the ground floor of a building. ‘It has just three steps’, I am told. Three damned obstinate steps and a metal barrier dividing the doorway, making it far too small for the wheel chair to fit through! Small needs, such as going to a local shop, can be difficult as most places are not wheelchair accessible. Even with a motorized wheel chair, navigating the kerbs is not always easy. Notwithstanding the autonomy which my wheelchair gives, the structural amnesia of the state and society with regard to built environment still impairs the determination of disabled people to be independent.

In my adult life I came to understand how illness is given significance and consequently comprehended and experienced through socio-cultural processes.

Diagnosis of Rheumatic Heart Disease

In November of 1968, I got sick with rheumatic heart disease. My mitral valve got damaged, resulting in an open heart surgery in 1980. What is significant is that the surgeon asked for a tissue valve. I should qualify that this tissue valve replacement meant that I did not have to take blood thinners. Long-term use of blood thinner medicine carries a risk of serious bleeding complications. However, the doctor did not bother to inform my father that such tissue valves require another valve surgery. Consequently, the valve gave way and in 1988, I underwent an urgent second heart surgery to get a mechanical valve. Now I need constant blood thinning. I was saved but the whole experience left me with questions about the power and status of the medical profession and also about the social and political basis of any illness. Surgeries also took away the “natural and prestigious roles” such as marriage and motherhood.

Disability, Cancer And Relationship With My Body

I had difficulty coming to terms with my illnesses but I never lost my sense of humour or the ability to smile. In 2005, a mammogram confirmed second stage breast cancer. Trauma was really an understatement. It was as if cancer broke up my fused thread of temporality – past converted into present, and future lost all its significance. Disability and cancer changed the relationship I had with my body. My intermittent fight with polio was not as terrifying, daunting and inexplicable as cancer. Cancer created questions; some of the hidden realities of my body were to become even more transparent than polio could ever make them. I had to acknowledge that this time my enmity was with a formidable foe. There have been times when I took exception to the word, survivor. It was funny as I had thought of a litany of terms such as cancer, polio and mitral valve fighter; an illness soldier; a winner of suffering, among others. However, my internalisations would not allow me to play the victim. I stood up for myself and explained that being disabled with multiple issues is a part of who I am. But, of course, it was not easy.

Yet, my disabled self was very intact, though marked by scars in many ways. While tears are always cathartic, resisting oppression became my theme song. That the personal is political became the slogan of my active struggles against the subjugations that I had to confront because of undesirable societal attitudes towards disability.

Being Independent Was Critical

A colleague once asked me whether I believe in miracles. When I responded in the affirmative, she was taken aback and said, ‘ask for a miracle to be cured of polio, then’. Strangely, this never really occurred to me. I had no memory of an able-bodied self. I also treasure the valuable experience that I can carry through life. I can’t imagine what my life would have been like if I didn‘t have polio and the other illnesses. I think it is telling that finding a cure was not my real fantasy. Being independent was critical. Once I obtained a permanent job, there were new questions that confronted me: Will I be able to drive? Will there be a man to love me and take care of me? What kind of fun and excitement will I experience? Would intimacy be real? Would I be a mother? As a young woman, I did not verbalise these questions as I knew that such roles will not be available to me. However, I reframed my questions as disability is not a curse. I realised that no one can fulfil all their desires. If one does not empathize with a disabled subject and personhood, one will not be in a position to understand the intimate core of my disabled self.

Sohna, a small village near Delhi is famous for its sulphur springs which are believed to have curative qualities for various stress-related ailments. These springs are located at the base of a vertical rock covered by a dome believed to have been built in the 14th century.

Anita Ghai is professor in School of Human Studies in Ambedkar University, Delhi. Her interests are in the intersection of disability, psychology and gender. Anita has researched issues of care of disabled women recipients and providers of care. She has authored Rethinking Disability in India, Routledge, New Delhi (2015), (Dis)Embodied Form: Issues of Disabled Women (2003) and co-authored The Mentally Handicapped – Prediction of the Work Performance with Anima Sen.

First published on Cafe Dissensus

Images sourced from the Internet