Nandini Murali, author of Left Behind: Surviving Suicide Loss, talks about the death of her husband by suicide, her voyage through the oceanic grief and her intervention strategies that kept her firmly buoyant. Read the second part of her interview. Read part one here.

Has writing the book Left Behind: Surviving Suicide Loss, after the death of your husband, been a healing and cathartic experience for you?

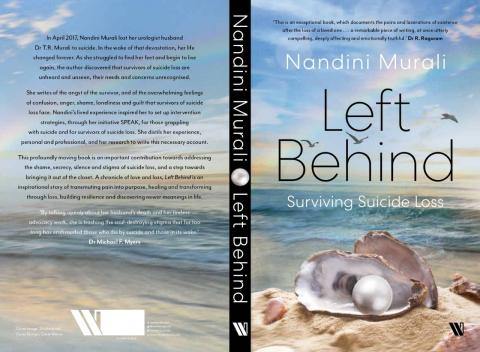

Oh absolutely! It has been transformative. I experienced great joy and satisfaction when writing the book. Of course, there were great many moments when I would be overwhelmed by a gamut of emotions. But while writing I would ground myself in equanimity, in a sense of joy, in a sense of calmness. That is the resonance I want in my readers. So it has not been just cathartic, it has been like a deep dive into the ocean of my being. At the end of writing the book, at the end of the one year journey, I literally came up with pearls of wisdom from my underwater exploration, a scuba diving of the psyche, if I may say so. I loved what I saw. It wasn’t easy. It has been a great adventure. I am glad I decided to embark on this very challenging journey. It was a journey without maps. No GPS, except the odd lighthouse.

The grief process for people bereaved by suicide can be complex and traumatic. What helped you most in ‘discovering newer meanings in life’?

Undoubtedly! It is profoundly isolating. It is mysterious. It is puzzling. And even for me, I had no idea that there is so much of complexity involved. I discovered new meanings in life, I would say through, my extensive reading around the subject, my grounding in feminist consciousness and in religion and spirituality. That gave me tremendous courage and strength. Even if I faltered, it gave me the courage, the resilience to rise up every time I fell. Of course there was my enormously loving and supportive birth family and a few friends who are a family to me. So these have been my biggest enablers. My spiritual guru whose wisdom and loving kindness shone like the full moon when I was voyaging alone, swimming in oceanic grief.

How does one take care of oneself whilst mourning for someone? What did you do?

I would call myself a poster woman of radical self-care because, while my grief was tumultuous, I also felt that it was very important to take adequate care of myself. Because I had to run a marathon, a grief marathon, and if I didn’t care of myself I wouldn’t have made it to the finishing line.

What did I do…I ensured I ate well. I rested well, I had nourishing food. I had plenty of water, I was well hydrated. Though in the initial stages, there was complete loss of appetite. Also, I stayed with my feelings. I felt I had to embrace my grief. I never ran away from the grief. I faced grief headlong. When I felt like crying, I cried. I didn’t resist the strong emotions surfacing within me.

Then I was very kind of to myself. I treated myself with the utmost care and compassion because if I didn’t do that, I felt I was marginalising myself. I did a lot of adult colouring. I listened to plenty of music. I love wildlife and wildlife photography, so I spent a lot of time with nature. That was truly healing. I sought out online support groups. And of course I had my loving family and friends who were wonderfully supportive.

I also made some changes in the physical environment in the house where I continue to live. I had it repainted, I shifted furniture and moved things around. Most importantly, I explored traditional systems of healing like acupuncture, yoga, yoga therapy and marma therapy which is Ayurvedic body mind massage. My spirituality and my daily pujas and prayers helped. And then I wrote extensively. And read voraciously about suicide and suicide loss. I think knowledge empowers truly.

Could you spell out certain sensitive ways to strike up a conversation on suicide loss?

Essentially avoid being intrusive. We understand your curiosity gets the better of you, of most people, but it is so important to be sensitive, to be respectful of our dignity and privacy. And not just indulge in morbid voyeuristic curiosity or conversations. Most people find it challenging to come up with the right words to condole with a bereaved person. And suicide, however, brings out the worst in people. Some norms of suicide bereavement etiquette based on compassion, concern and care may help provide a roadmap to navigate conversations on suicide loss.

- Don’t ask intrusive questions about the manner and mode of death.

- Don’t use hurtful clichés like ‘This too will pass’, ‘You must be strong’.

- Don’t assign or imply blame. Say ‘You were a great support’, ‘It is not your fault’.

- Don’t make statements such as ‘Suicide is an act of cowardice’ or ‘Suicide is the result of selfishness’.

- Don’t give us unsolicited advice.

- Don’t condole with us just because it’s the thing to do.

- Be proactive. For example, you can include us get-togethers or call to find out how we are.

- Simply listen. Telling our stories over and over again is one of the ways in which we heal.

What are some of the best ways to support someone bereaved by suicide?

I would say…be there for the person unconditionally. Know what to say and what not to say. Extend the space of no judgement, compassion and concern. I think it is not so much about the words, it’s about how you communicate, it’s about the body language. How do you communicate that you are there for the person. When people say… ‘Oh I know how you feel’ that sounds so glib. Because you never know till you have gone through the experience. Or you can say, ‘I don’t know what to say, but I am there for you and I am ready to help you.’ That sounds authentic.

And listen to us. Avoid intrusive questions like… ‘Tell us what happened.’ The need is to have a safe supportive space where we feel we are seen and heard.

You have concluded the book on an optimistic note that even ‘monumental sorrows can be left behind, one step at a time’. Is this one of the big takeaways of Left Behind?

Yes, of course. And the other big takeaway of Left Behind is that we have no control over what happens to us, but we have every choice and every control in choosing how to respond. That for me is one of the biggest takeaways. Between stimulus and response there is a gap, and that’s where our choice, our free will lies. And also I believe Left Behind tells us that no matter what happens, even the most challenging circumstances, there is a way out, there is a sliver of hope, and lights that can filter through in the darkest of caves, even the abysmal oceanic depth. We need to search for that, we need to find that.

I think to end dukha caused by a tragedy like this is to turn inwards and the healer is within us. I have connected with the Supreme Healer within. And so the journey continues. My healing is far from complete. It is still a work in progress. The journey continues. The message that I would like to send is that we, who have lost a loved one to suicide, should cherish the memories of our loved one. It is a sacred legacy for us, it is a treasured memory. We don’t move on in life. We move through the loss, we move through the tragedy, one step at a time. And monumental sorrows can be left behind. I for one do not want to be seen as an icon of resilience or a phoenix rising from the tragedy, but I think I would like to be remembered as an ordinary person who had to face an extraordinary challenge who did it with the best of her ability.

We need to bring suicide and suicide loss, subject which nobody talks about, in the public domain with informed perspectives. Because I feel the suicide prevention discourse in the country has the convergence of several stakeholders mental health professionals, health care professionals, media, law enforcement, judiciary, activists, policy makers, NGOs, but where are the people with lived experiences with suicide, or suicide experiences, either suicide attempts or suicide survivors. And I feel in writing Left Behind we have so much of wisdom and insights because we have seen things up close and personal and we could augment the clinical perspectives of mental health professionals and other stakeholders.

And I think another big takeaway of Left Behind is how to humanise this issue (of suicide and suicide loss) and rather than criminalise it. It is a very perplexing, complex yet pervasive deeply personal issue. We need to open up spaces for candid conversations about a subject which is so shrouded in taboo and toxic silence. I think it is time to change those narratives. And that’s what Left Behind tries to do.

(Dr. Nandini Murali is a suicide prevention and mental health activist. Her lived experience of suicide loss inspired her to establish SPEAK, an initiative of MS Chellamuthu Trust and Research Foundation, Madurai, and SPEAK2us (9375493754), a mental health helpline for people in psychological distress.)