Rima Pande in her debut novel, His Voice, writes a fictionalised narrative about the teeming thoughts swirling in her father’s mind for two years as he lay conscious but paralysed and unable to speak due to two successive strokes in a month. There are great insights into caregiving. Read it.

Could you tell us a little bit about the experience that led to your writing ‘His Voice’?

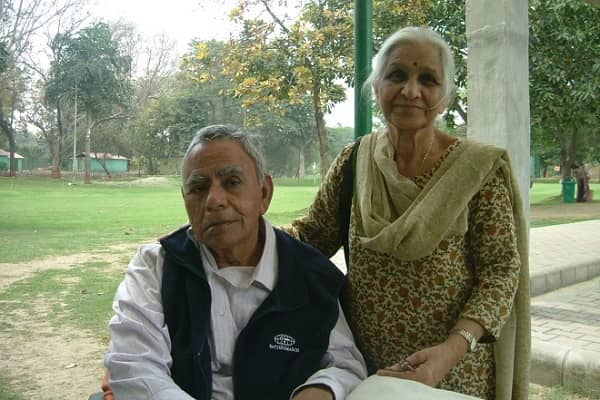

My father had two successive strokes within a month, leaving him paralyzed and unable to speak or communicate in any manner. For two years, my mother served him, supported by amazing family, friends and helpers. We stared at the constantly changing expressions on his face for clues - was he too hot, too cold, in pain, hungry, uncomfortable, attentive, tired, sleepy, somewhat happy? We searched for direction, pretending to understand what he would like us to do, doing it, then searching for an imperceptible nod of approval. When he slept, I wondered what was going through his mind, trying to immerse myself in his stream of consciousness.

My book, His Voice, is a first-person narrative of my father’s unspoken thoughts and emotions during the two years he lived after his debilitating stroke. The narrative of his current state is interspersed with memories of key life experiences that shaped him as a person, making it a memoir or life story of sorts.

Writing this book started a therapeutic experience for me, it helped me deal with a bunch of emotions that come with such life experiences - confusion, denial, hope, frustration, grief, regret. I really missed my father. His death, even though we had two years to “prepare”, created a giant vacuum in my life. I wrote the book a few months after we lost him, did not share the manuscript with anyone till 2020 when I drummed up the courage to have a few people read it, and hesitatingly decided to publish it.

You have immersed yourself in your father’s consciousness and articulated his thoughts and feelings. Was it intimidating to step into his shoes and assume his perspective?

Caregiving comes with a multitude of physical, mental and emotional challenges. I personally also struggled with finding the right balance between worrying about my father’s situation and continuing to live my “normal” life in Boston - work, home, kids, vacations. It was hard to travel back each time, and I dealt with it by planning my next visit to Delhi as soon as I landed in Boston.

My writing was driven by my need to imagine what was going on in his mind, especially as he had no way to express himself except through emotions on his face. And understand him as a person, especially how he was dealing so calmly with this monumental crisis, how he was channelling mental strength and positivity to continue the effort and not give up.

The decision to publish the book was intimidating. Till I realized that storytelling is a powerful medium to shed light on social issues without sermonising, and stories resonate with people and make them think and reflect.

You were shuttling between Boston and Delhi every two months to be with your ailing father. How can one best provide emotional and psychological support remotely? What has been your learning?

My mother was the primary caregiver, supported by family and friends, mainly her siblings. For me, managing my own emotions, and the amplified sense of regret and guilt was critical so that I could do my best as a “secondary” and “long distance” caregiver.

I travelled back and forth from Boston a lot during the two years my father lived after the stroke, and spent a lot of time in Delhi. While with my parents, my role was as a “secondary caregiver” - helping with planning, assisting when I was there, and most importantly supporting the primary caregiver, which is critical. It is important to help without imposing your own views, and make the primary caregiver feel empowered and confident. I was also the research assistant, reading about his condition, medications, possible approaches to taking care of him, potential opportunities for innovative treatment, exploring clinical trials etc.

The journey back to Boston each time was hard, accentuating the guilt considerably, and the only way I dealt with it was by planning my next trip pretty much as soon as I got back home. And by calling every day on my way to work to chat with my father (a one-sided conversation of course) and my mom. Another challenge for me was finding the right balance between worrying about my father’s situation without it impacting the other people in my life, and continuing to give them full attention - household, kids, work … you can put your life on hold for short periods, but when it is uncertain how long a situation will last, you have to find a balance.

Your book celebrates family togetherness and parental love. What were the two overwhelming aspects of looking after your father?

His physical helplessness was one. In situations where there is physical infirmity or mental impairment, there is a physical aspect to caregiving. In some cases, a person just needs help with what are called activities of daily living. At the other end of the spectrum, like in my father’s case, he was paralyzed neck down, so anytime he had to be moved, whether in the bed, to the wheelchair or back, was an event that required thinking, planning and at least two strong able-bodied people. He did have the ability to eat orally, move his head and more importantly, even though he could not speak, gesture, write, he could emote. For my mother, a major practical issue was that she could not move him independently, and her efforts took a toll on her.

The second was his inability to communicate. He could not speak, point, gesture, write or draw. He also could not tell us how he was feeling, whether he was hungry, thirsty, cold, hot, uncomfortable. For example, If someone was not watching, he could not tell us to swat a fly sitting on his nose. There was also a real risk of injury. If someone was not paying attention, and his foot slipped off the rest while he was being pushed in a wheelchair, his foot could drag on the floor, twist or even worse. Once, when he was admitted in the hospital after a seizure, his hand got compressed by the rails on the side of the hospital bed for a few hours, and no one knew till the blanket was removed. So it was imperative that someone watched him all the time, and made sure he was safe and comfortable.

Your mother, who was the primary caregiver, always maintained a positive and loving environment around your father. What can the reader, especially those looking after a terminally ill patient, imbibe from her?

My mother, after the initial shock, moved very quickly into action with an “everything will be fine” attitude. She naturally assumed the role of primary caregiver, she led by example, she focused herself completely on planning and managing his care, was unfailingly positive and encouraging - driven by her faith in god, and her personal sense of discipline. Beyond the physical care, medications and therapy, she created a happy place which buzzed with activity and positive energy. There was conversation, music and laughter. We sat around in his room, ate meals at the dining table together, parked him in the living room in the evening. He was enveloped by what my book editor calls a “circle of love and care”.

In hindsight, his situation was a great example of palliative care in action, i.e. paying attention to the patient’s thoughts and feelings, and making decisions that are best for the patient, with a focus on quality of life, reduction of pain and discomfort, and most importantly, peace of mind. My father got the care he needed. He was given antacids to keep his digestion comfortable, he was given anti-seizure medications, he was given anti-infectives to avoid infection. He was physically well taken care of, got regular showers/ therapy/ massages, was mentally stimulated and emotionally nurtured. But we also decided that we would not rush him to a hospital and avoid major interventions that would make his quality of life worse rather than better.

During these two years, I had a strong support system. My husband took care of everything when I traveled to Delhi, my kids independently managed when I was gone and went with me to help during two summer vacations. Ironically, while I struggled to come to terms with what had happened, my mother continued to be my strongest support system, mainly by virtue of how she handled things, staying strong, being practical and realistic, never putting any pressure on me, helping me manage my guilt by encouraging me to focus on my life.

You have mentioned that writing this book has been a therapeutic experience for you. How has it helped you heal?

Writing this book definitely started a therapeutic experience for me, it helped me deal with a bunch of emotions that come with such life experiences - confusion, denial, hope, frustration, grief, regret. I really missed my father. His death, even though we had two years to “prepare”, created a giant vacuum in my life. I wrote the book a few months after we lost him.

Writing helped me overcome the many regrets coursing through my mind - I felt like I understood him a little better, knew him a little better. Writing also helped me deal with the sadness, it made him come alive for me in my writing. Recounting the experience also helped me crystalize my learnings into the 4R framework of caregiving that I talk about. And sharing my father’s story and learnings continues to be therapeutic.

How did you handle the crippling anxiety of impending death?

My father was physically well cared for, mentally stimulated and emotionally nurtured in the two years after his stroke. Even though he was immobile, his condition did not deteriorate due to the care he received. For the first year, he showed minor signs of improvement, offering a glimmer of hope. During the second year, he was not improving but remained stable till the last few weeks before he passed away, when he stopped eating properly and his spirit seemed to sag. There was little hope of recovery. I had very mixed emotions as I thought about him living in a state of complete helplessness/ locked into a non-functional body for years, and realized that death may actually bring release from the prison his lifeless body had become. When he passed, he was surrounded by love and prayers. We rationalized the vacuum his death created with the thought that he was in a better place.

How has your experience as an end-of-life caregiver affected the way you live your own life?

Being up close and personal with end-of-life care has enhanced my awareness of human frailty and how tenuous life is, how quickly life can change for any one of us. I have a clearer appreciation for and increased ability to focus on what’s important. I think my definition of family has evolved, and I am more willing to invest time and energy in connecting with people who are important to me. I also think my ability to deal with diversity has improved, I am less likely to panic and more likely to react thoughtfully to difficult situations.

Atul Gawande in his book ‘Being Mortal’ writes: ‘Our ultimate goal, after all, is not a good death, but a good life to the very end’. What is the importance of patient dignity in care at the end of life? How did you ensure dignity and respect for your father?

The 4R framework emerged naturally from my observations and learnings during the two years after my father’s stroke. In summary, there are 3 key principles or tenets of caregiving - Respect, Resilience, Realism, built on a foundation of a fourth R - Relationships.

Respect. Paul Kalanithi in his book ‘Till Breath Becomes Air’ said - “until I actually die, I am still living”. As a person becomes more helpless, their sensitivity to everything said and done becomes more acute. One of my key learnings was how important it is to maintain the dignity of a person who is in a helpless state. My mother set a positive, respectful, uplifting, happy tone in the house for my father. He was part of everything that happened - treated with deep love and respect. I believe that made him as happy as was possible given the circumstances.

Resilience is about working with what life throws at us without breaking down. It takes an immense reservoir of courage and compassion to stay calm when your world is falling apart, to be loving and unfailingly patient, without it becoming deliberate or wearying. We have to find our strength in the way it works best for us. My mother was driven by her faith in god, her belief system “whatever happens happens for a reason”, “it is god’s will”. Her faith gave her physical, emotional, mental energy.

We also need a dose of realism, understanding that effort may not always yield the results one hopes for, while not giving up. We cannot fix everything, sometimes we need to manage it to the best of our abilities, while balancing hope and optimism. As the Gita says “Karmanyev adhikar asthe, ma phaleshu kadachana”

Relationships - spousal commitment, the parent-child bond, family support, many intersecting and distinct circles of friends. In the book Blue Zones, Dan Buettner investigates the world’s healthiest communities. In addition to diet and staying active, one of the common threads among all these communities is a strong social fabric and sense of connectedness among inhabitants. Medical crises make one more acutely aware of the invisible bond that connects families even as everyone leads separate and often geographically scattered lives, as well as brings to the fore one’s links within one’s local communities as neighbors, and people one least expected are there for you. It also highlights the importance of nurturing and maintaining family and community relationships. My mom was able to do what she did because she had her family’s (especially her siblings’), neighbors’ and friends’ physical and emotional support through her caregiving journey.

What is the inspirational takeaway from your book for readers?

I hope the book will help folks pause, acknowledge and appreciate the key relationships in their life. I hope they will think about how they view and interact with people who are not fully functional. I also hope folks will reflect on the 4R framework (Respect, Resilience, Realism and Relationships) which highlights the key tenets that one needs to keep in mind when faced with a healthcare crisis. And remember what Paul Kalanithi said “Until I actually die, I am living”.

Remember, caregiving has immense power to make someone else’s life better. And it is the simple stuff that counts. “We can all make a difference in the lives of others in need because it is the most simple of gestures that make the most significant of differences." ― Miya Yamanouchi

Author bio: Rima Pande is a healthcare strategy consultant based in Boston, with a strong passion for human-centered healthcare, nutrition and equitable socio-economic development. Rima has recently published a book titled "His Voice", a journey through her father's mind to share his unspoken thoughts and emotions during two years he was paralyzed and unable to speak after a stroke. Available on Amazon in all markets. For more information on the book, author, buying options, news and events, please visit https://www.hisvoice.life/